The Best ‘Toy Story’ Is Still the First One

If you look over a list of the greatest animated films of all time, or at least the greatest Disney animated films of all time, you’ll likely find Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs near the top of the ranking, or possibly holding the top spot. The 1937 film is inarguably one of the most influential films of all time, setting the template for how animated storytelling could work, both visually and in terms of character development and plot. But — though your mileage may vary — I’d argue the film is important for setting a template that other films improved upon. Snow White walked so Pinocchio and Dumbo and Sleeping Beauty could run.

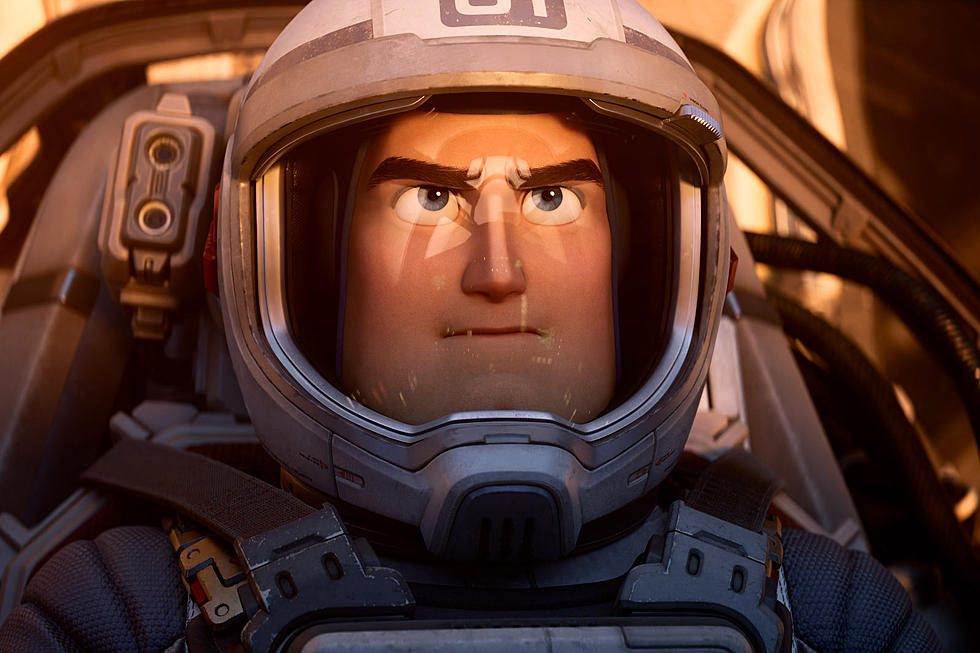

But sometimes, setting the template means setting the bar so high that everything else can only hope to top it. Take, for example, the other animated film that’s as influential as Snow White: Toy Story. It was the first of its kind, a true original, proving that computer technology was just as viable for making animated features as hand-drawn animation was. Toy Story introduced the world to a unique blend of visual and storytelling style that felt fresh even as it utilized familiar action-movie tropes. And the 1995 animated film unveiled a group of beloved characters who are getting yet another moment in the spotlight with Toy Story 4 this month.

But Toy Story isn’t just the first. It’s, at least to me, the very best film a) in the Toy Story franchise, and b) Pixar has ever made.

To be clear, I’m not going to argue that Toy Story is the most beautifully animated film Pixar has ever made. It is decidedly not, and how could it have been? The technology used by the brilliant animators at Pixar has moved far beyond what was on display in the fall of 1995 when a pull-string doll named Sheriff Woody first got jealous by the arrival of a flashy space toy named Buzz Lightyear. Visually, Toy Story has been lapped by literally every other film Pixar has made. Even the 1998 film A Bug’s Life looks better.

But looks get you only so far. Toy Story sets a very important template that many of the films that followed from the studio would utilize: the buddy comedy. As has been written in the David Price’s book The Pixar Touch, the film’s director, John Lasseter, and animators like Andrew Stanton and Pete Docter, were encouraged to review one of the ultimate buddy-comedy classics, 48 Hrs., in building out the relationship between Woody and Buzz.

And it shows in the final product. Woody meets Buzz when the former is unceremoniously thrown under the bed by his owner Andy, who’s excited about the popular new toy he received for his birthday. Soon enough, Woody’s jealousy mounts, to the point where he tries (and fails) to trick Buzz into falling behind a desk. After Woody’s plan goes awry, both he and Buzz wind up stranded at a gas station far from their home. The sheriff and the spaceman are about as mismatched as they get, forced to work together to achieve a common goal while also coming together as fast friends whose bonds can’t be shaken.

That last description, of course, applies to a lot of the dynamic duos in the rest of Pixar’s films. Joy and Sadness in Inside Out. Remy and Linguine in Ratatouille. Marlin and Dory in Finding Nemo. Mike and Sulley in Monsters, Inc. Lightning and Mater in Cars. Carl and Russell in Up. There’s a lot.

It’s not just that Toy Story inspired a slew of other buddy comedies from Pixar. Setting this template has served Pixar well through various distinctive premises. From monsters to fish to a boy traveling in the world of the undead, there’s an inherent strain of buddy-comedy in Pixar films that began with Toy Story. But Toy Story boasts a complex script with a multidimensional lead character whose arc through the film is carefully constructed and designed. Woody’s arc, in which he not only comes to accept that Buzz Lightyear is a good toy, but he even proudly shouts out Buzz’s tagline (“To infinity and beyond!”) by the end, is all the more remarkable because of how rocky the production was for Toy Story.

Though it instantly became a massive hit in 1995, there were a lot of obstacles during the making of Toy Story. In November of 1993, almost two years to the day the film would open in theaters, production was shut down because, among other things, the core relationship between Woody and Buzz just wasn’t working. The heroic sheriff seemed too nasty. He was toned down after production reopened, though even in the final film, Woody’s bitterness about being replaced is tangible and potent.

But Woody’s not a wholly cruel character, as charming and kind as he is selfish. That depth of character is as much thanks to the script as it is to Tom Hanks’ brilliant and hilarious performance. (I’m here to tell you that Tom Hanks is at his best when he’s funniest, and he has not been given the chance to be this funny ... well, since the first Toy Story.) The Toy Story sequels expand upon Woody’s character, but the humor of the character is at its peak in this movie, because Woody’s never more frustrated than he is when dealing with Buzz the first time around.

This ties to something else that is very key to what makes Toy Story so immediately iconic: Its exceptionally funny, quotable script. There’s Woody’s spluttering response to Buzz in the throes of his belief that he’s a real spaceman: “YOU. ARE. A. TOY!” (This comes after Woody mocks Buzz, when he realizes that the toy thinks “he’s the real Buzz Lightyear! Oh, all this time, I thought it was an act.”) But just about every character in the film has a handful of lines that are extremely funny and memorable, some of which are key to defining who they are as characters.

The script (credited to Joel Cohen and Alec Sokolow, Andrew Stanton, and Joss Whedon a couple years before the TV version of Buffy the Vampire Slayer vaulted him to cult status) channeled its performers exceptionally well. You only have to hear Mr. Potato Head speak one or two lines and recognize the distinctive personality and voice of the late Don Rickles, and also fully grasp who this character is. (It helps that one of Mr. Potato Head’s first lines is “What are you looking at, ya hockey puck?”, a Rickles-ism from his decades of stand-up that still works in this family film, in part because Mr. Potato Head is literally talking to a hockey puck.)

The same goes for the neurotic dinosaur Rex, voiced by the nebbishy Wallace Shawn; the loquacious piggy bank Hamm, voiced by John Ratzenberger; and Woody’s faithful friend Slinky Dog, voiced with a Southern drawl by Jim Varney. These characters are all important supporting players — though Varney and Rickles have both passed away, the characters of Rex, Hamm, Slinky Dog, and Mr. Potato Head are in all four films — and they’re instantly defined through only a little bit of very sharp dialogue. It’s a wonderful, impossible-to-find mix of acting and writing.

Perhaps the genius of Toy Story, and a level of genius that hasn’t been topped by other Pixar films (though many come close, to be clear), is that the script is extremely economical while never feeling rushed. Including end credits, this film is just 81 minutes long, which is long enough to establish the world of the film, its inherent conflict, character relationships, and more, all without feeling clinical or like it’s following a pre-existing template. That last point is worth noting, because in a lot of ways, this film ... is following a pre-existing template.

According to The Pixar Touch, during the production of Toy Story Lasseter, Stanton, Docter and Joe Ranft took it upon themselves to attend a three-day screenwriting seminar overseen by the legendary industry figure Robert McKee. (You may remember McKee from the Charlie Kaufman film Adaptation., portrayed by Brian Cox.) McKee argued that a good script had a clear, definable three-act structure, expanding upon ideas made clear by Aristotle. Though McKee’s teachings and seminars have been criticized, and a traditional three-act structure can feel stodgy, it’s clear that the Pixar story team took his message to heart. Toy Story really does have a clear structure. Yet, when you watch it, the film is so swiftly paced, smartly written, funny, and exciting that its structure is easily hidden.

Though the film’s main villain is Sid, Andy’s destructive next-door neighbor, the final action sequence occurs after Sid has been permanently traumatized by the sight of inanimate toys coming to life to scare him away from ever attacking them again. Woody and Buzz are desperate to catch up to a moving truck with all of Andy’s toys, headed to a new house. The other toys still think Woody has nefarious plans for Buzz, so they’re not willing to help him; eventually, Buzz and Woody take off on a tiny rocket Sid had intended to use to blow the spaceman toy up, riding a remote-control car through the tri-county thoroughfare.

The return of the rocket is one thing, but then, as Buzz and Woody are lifted high in the air by the rocket, comes a combination of payoffs. First, Buzz opens up the wings on his back (wings he’s already tried to use to fly, to no success, in Sid’s house, thus tragically accepting that he’s just a toy), and he and Woody start flying. Or, as Buzz dryly corrects Woody in a recurrence of an early insult, “This isn’t flying. This is falling. With style!” And then Woody freely echoes Buzz’s tagline, in a moment that could have felt calculated — a culmination of McKee’s three-act structure and Woody’s character arc — but instead feels triumphant.

This, perhaps, is the special quality of Toy Story that no other Pixar film can claim: it managed to represent a fusion of writing and technical style that was both inherently recognizable and entirely new. Every other Pixar film, many of which are excellent, had the mild misfortune of following this act. Technically speaking, every other Pixar film is an improvement upon Toy Story. But creatively, in terms of character development, wit, and ingenuity, the first-film jitters of Toy Story wound up turning the film into something truly, unforgettably special. The sequels are both quite wonderful in their own ways, paying off on years of emotional connection. But the first Toy Story is the one and only, establishing how far beyond infinity the studio could go.

Gallery — The Best Film Series in History:

More From 97 ZOK